1 Canadian Special Wireless Section (Type B) (CE Newsletter Article)

The Untold Story of Number 1 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type "B"

As told by Mr Ron Gates to Colonel C.J.Weicker. Director Information Management Requirements [1]

Contents

- 1 Canadian Special Wireless "Scoop" Warns of Elite German Armoured Counterattack

- 2 Canada's Special Wireless Story

- 3 Canadian Special Wireless Units Role

- 4 Canadian Special Wireless Units

- 5 Canada's First Special Wireless Unit

- 6 Formation and Training in Canada

- 7 In Defence of England

- 8 Fighting on the Battlefields of Italy

- 9 Joining the 1st Canadian Army in Holland

- 10 Conclusion

- 11 Notes

Canadian Special Wireless "Scoop" Warns of Elite German Armoured Counterattack

In May 1944, the Allied forces fought a vicious campaign to crack the series of formidable German defences defending the city of Rome. On 11 May, the breakthrough of the Mount Cassino front was planned.

Signalman Ron Gates was on duty in the intercept van that eventful night. At approximately 2100 hours. the German wireless nets went on listening watch for the night. "It was so quiet it was eerie".

At 2300 hours a massive artillery barrage announced the start of the Allied attacks.

"The German nets quickly came active in response. As the crushing artillery fire continued the Canadian Special Wireless operators were able to make numerous interceptions in plain language Morse code or in plain voice, which were quickly patched to the Intelligence van for exploitation."

However, the sources of many of these transmissions were from German units in contact along the front line. The Canadian operators continually tried to pick up any indication of the move of reserve German units that could potentially stop the Allied advance.

By the 16th of May, the first line of defences, the Gustav Line, was breached and the German troops were streaming back to the next line of defence, the Hitler Line, straddling the Liri Valley. At this point, the 8th Army Commander, Sir Oliver Leese, ordered the Canadian Corps to pursue the retreating Germans and breach the formidable Hitler Line before they had time to properly occupy their defences. Their attack up the Liri valley was focused on seizing the Italian town of Pontecorvo. Unfortunately, the Germans were able to occupy their well-camouflaged defences in front of the Canadian advance and ruthlessly stopped the Canadian's hasty attack.

After a three-day pause for preparations, the 1st Canadian Division launched a deliberate attack up the narrow Liri Valley behind a massive artillery barrage. A half-hour later the Americans launched their long awaited breakout from the Anzio beachhead, south of Rome, hoping to cut-off the German troops locked in battle with the Canadians. As the Canadians advanced they took heavy casualties in the Division's hardest day of fighting in the Italian campaign. The success of the operation hung in the balance throughout the day. In desperation, the Germans ordered the Herman Goering Division to counter-attack southward during daylight in the hopes of avoiding detection, despite the Allied's air supremacy.

It was during this critical period of the battle that Signalman Ed Marten intercepted a message from the Herman Goering Division indicating that it was on the move. He quickly recognized the significance of the message and relayed it to the Intelligence van. The Intelligence operators quickly passed the message up to Corps HQ who rapidly informed Mediterranean Allied Air Force; while disguising the source of the Information.

The early warning of the move of this elite German Panzer Division allowed for the rapid concentration of all available fighters and fighter-bombers. The Herman Goering Division was subjected to relentless low-level attacks causing considerable losses. The result was that it took them three days to reach the front. Leaving behind a litter of blackened twisted wrecks of tanks, trucks, guns and troop carriers. The threat to the Canadians had been stopped in its tracks!

Ed Marten's intercept had caused a chain of events that possibly saved many Canadian lives. Due to the secrecy surrounding the unit, Ed Marten received no official recognition for his actions. Even today, the fact that a Canadian Army Special Wireless (SW) unit was responsible for making the initial warning of this potentially deadly counter-attack has never been recorded.

Canada's Special Wireless Story

The first official history of Canadian Special Wireless (SW) was not made public until 1986, over 40 years after the events, due to security. It was written by Captain Norm Wier and was based on interviews with Captain Bill Grant, CO of No.2 Canadian SW Section Type "B". It is an extremely detailed and well-written account of that unit. An electronic copy has recently been posted on the Communications and Electronics Branch website. Unfortunately, it provides little detail about the experiences of its parent organization - No, 1 Canadian SW Section - Type "B".

For myself, the history of this unique Signal unit is also personal, as my father, centre, joined the unit in September 1942 and was eventually employed as the unit administrative clerk.

The veil of secrecy surrounding this first SW unit can now be lifted in order to commemorate years later the actions of its members as they fought their secret battles during World War Two as the first of Canada's "Spies of the Airwaves".

Canadian Special Wireless Units Role

The role of the SW or "Y" units was to produce INTELLIGENCE for Canadian Army Intelligence staffs. "Y" units consisted of three types:

Type "A": were concerned with providing general interception of enemy signals to produce wireless intelligence for Intelligence staffs at Army HQ and Y information for other Y units. They provided Direction Finding (DF) results for use at corps, army and GHQ levels. They were also tasked to conduct forward interception of strategic material for research at the GHQ level.

Type "B": provided short-range interception and DF for Corps HQ. They were focused on the interception of material from enemy wireless links that can be dealt with on the spot. This included enemy reconnaissance reports, army-air cooperation traffic, and to forward supply links and messages in clear or simple codes between the enemy's lower formations. It used DF to locate enemy units at the tactical and operational level. In static operations this information became reliable to a high degree, especially when correlated with information from Y units along flanks and to the rear, combined with other intelligence sources.

Special Wireless Group: provided the higher-level support for a both Type A and B units, including the holding of stocks of equipment and spares, and the conduct of signal and intelligence training.

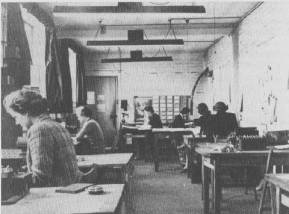

Organization: Each "Y" unit was comprised of a SW Section and a Wireless Intelligence (WI) Section. It was essential that all personnel of the SW and WI sections considered themselves as ONE UNIT and work in complete co-ordination and community of interest.

The SW Section consisted of 2 Signal officers and 76 men. The men of the SW section were signal operators, drivers, dispatch riders, technicians, cooks, storemen and an administration clerk.

The WI Section consisted of three Intelligence Officers, a Sergeant and eighteen German linguists and analysts.

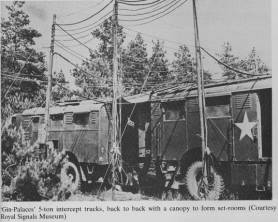

Interception: There were two set vans for intercept, as well as Intelligence compilation and analysis van forming a "Gin Palace". The intercept vans each had 6 National HRO receivers, one Halicrafter UHF receiver and a No. 19 set.

The operators needed to know as much as they cou1d about the enemy's call signs, frequencies, signal equipment, codes, etc. The Germans changed both call signs and frequencies at midnight. They used Morse code and Q signals for their communications, thus there were no requirements for operators to speak German. Sometimes voice communications were ultercepted and these were patched directly to the Intelligence van where the German-speaking staff would eagerly listen to their unsuspecting enemy's conversations. The Germans used special operating procedures for certain units that aided in their identification. The German Army mainly used HF radios (1.5 - 4.0 MHz), but the Parachute Divisions used VHF radios (28 - 30 MHz) in the belief it could not be intercepted.

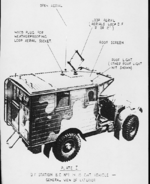

Direction Finding: The DF vehicles were based on 15-hundredweight wireless van with originally a loop aerial, however these were later changed for a Canadian design based on a vertical di-pole. The DF operator worked in the vehicle. In England there were cases where the DF equipment was mounted in civilian pattern vehicles to maintain security. DF accuracy could be as good as one kilometer square and when combined with the intercepted message could be better. All traffic between the DF controller in the Interception Set van and the DF detachments was prepared in code to maintain security.

Command and Control: The two sections functioned as one unit with the senior Signal officer as the Commanding Officer (CO), responsible for the conduct of the unit's administration, protection, movement and signal operations. The OC of the WI section controlled and assigned the frequency coverage of the various radios conducting interception and directed the conduct of DF tasks. Command of the unit was special due to the independence of the CO, who reported directly to the Corps Signal Officer. Having both Intelligence and Signals elements in the unit proved to be interesting. Corps Intelligence only wanted the intelligence output from the WI section and Corps Signals was responsible for the unit's training and administration.

Canadian Special Wireless Units

The Canadian SW effort was not developed in isolation but was based on British concepts, doctrine and organization. In fact, the British provided common training and equipment to all of the Commonwealth nations involved in this highly secretive activity. Throughout the war, twenty British, two Canadian, one Australian and one Polish SW Type B units were formed.

The Canadian Army formed two SW Type B units for each of the Canadian Corps, a SW Type A unit for the 1st Canadian Army and at the end of the war a Special Wireless Group. This unit was entitled Number 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group and operated in the Pacific Theatre in conjunction with the Australians and Americans. An article on the history of this latter unit was recently written by Sgt McCaffrey and pub1ished in the Communications and Electronics Newsletter 2000/10 Volume 41.

The remainder of this article is based mainly on information collected and provided by Mr. Ron Gates who was one of the original Signalman intercept operators with Number 1 Canadian SW Type B. He has been the driving force in keeping contact with all members of the unit. In the last twenty years he has written and distributed information on the unit and its personnel in the form of newsletters. He has encouraged and arranged numerous reunions in Canada and visits to England. He made contact with British author Hugh Skillen, and provided much detail on the history of his unit. This information was published in a collection of the histories of the Army Y Sections known as "The Y Compendium".

Canada's First Special Wireless Unit

On December 3 1940 the Director of Signals, Major Fairfax-Webber, issued a memorandum that a SW Section, Type B be formed under the command of Lieutenant Jack Anderson with Sergeants W.E. Grant and Lance Sergeant H.A. Whincup as its NCOs. The members of the unit were selected mainly from 5th Armoured Division Signals in Barriefield. Others came from Signal wings of the District depots across Canada. There were even four Americans who joined up in Windsor. Signalman Ron Gates arrived from Toronto on January 7, 1941.

Formation and Training in Canada

Since accommodations were not available at Camp Barriefield, Kinston, the unit was formed at Landsdowne Park in Ottawa.

"The operators were a mixed bunch, some former HAMS, some railroad telegraphers, some who had worked as ship operators, and one who had served in Spanish Civil War. Many had only basic Morse code skills."

The unit did all its training in the Ottawa area. Training consisted of basic electricity, radio theory and practice on HRO receivers, and improving Morse code skills. The wireless intelligence section did their own training separately.

They learned about the German Army organizations and radio procedures.

All members of the unit completed basic Army training by learning drill, map reading skills, and weapons handling, complemented with route marches (full pack).

In Defence of England

The unit left Ottawa and traveled by train to Halifax. They safely crossed the Atlantic on the MV Aorangi arriving in Glasgow, Scotland in Oct 1941.

"We traveled by train to Aldershot and got five days leave. Afterwards we went to the Special Operators Training Battalion in Trowbridge. All instruction was based on German wireless procedures (Q signals) and their radio net structure and call signs."

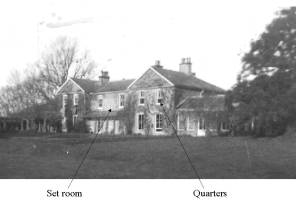

After training the unit was deployed to Bolney in Sussex where they set up operations in an old manor house. Here they relieved the British 106 SW Type B. This was the start of a close relationship between the two units.

"We were operational on Dec 24, 1941 and were told to copy all the "Enigma" traffic we could, as they told us that this code had not yet been broken. Really it had already been broken but they required everything they could get for verification and further intelligence. All the Enigma intercepts were sent by DR four times a day to Bletchley Park."

At Bletchley Park, the Canadian traffic was amalgamated with all the other intercepts of the day as part of a massive secret operation to break the German Enigma code.

The target for the operators was the German Army's Morse code communications between units located in France and Norway. Each operator had to maintain a log to record all the details of any intercepted message including the time of reception, the frequency, and call signs. The German radio procedures were based on international Q signals. The actual text of the message consisted of the Enigma ciphertext broken down into groups of five letters. The operators used a message form that was similar to the German message form. It was marked with the classification "TOP SECRET" in red ink at the top and bottom of every page.

The Germans were very confident in the security of the Enigma code. The German Army and Navy were the most disciplined while the Air Force was careless in selecting the initial setup letters for the Enigma. Since there was an Air Force Liaison Officer attached to each Army Division, much information about the German Army could also be decrypted through this source.

"Our daily Job was early in the morning to search the bands and listen for the Luftwaffe long-range aircraft conducting weather and shipping flights. The planes were known as Zenits. The importance of the identity of a Zenit was that by intercepting the first message sent, the frequency and call sign, all German Army and Luftwaffe wireless groups associated with each unit could be identified for the next 24 hour period. As soon as we had identified the Zenit, the information was sent to Bletchley Park in code over landline. Once the wireless groups were known, the focus shifted to intercepting German Army traffic for the rest of the day."

Of course, it was not all work, there was also time to go to London on weekend passes once a month. The soldiers also received a seven day leave every six months to travel throughout Great Britain. During this time. King George VI visited the Canadian troops, including the unit.

The unit was trained to conduct signal intelligence operations against the Germans. However, it was decided by Corps Headquarters that it might be a good idea to see how good was the Army's communication security. This proved to be a task with a few surprises for the staff and the unit.

"One of the jobs we were asked to do by GHQ was to monitor the Canadian Corps nets during a training scheme named "Tiger".

We moved our equipment close to the training area. The security of the nets was poor, for example, using names in clear and not following proper procedures. Our reports of their poor radio security was instrumental in that most, if not all of the Corps operators losing their trades pay of 50 cents a day (one third of your daily pay).

We were then rewarded with this action by being called into Corps Signal HQ to be tested for our operators' abilities on Canadian radios (which we had not been trained). Many of us could not pass the test on the operation of the transmitter, so they took our trades pay away. Captain Anderson went to Corps Signal HQ and complained about this unfair action and got all the operator's trades paid back."

During August 1942, the Canadians conducted a raid at Dieppe. The unit assisted the operation by relaying Information from the Germans back to Corps to aid them in keeping track of what the Germans were doing and what information they had on the Canadian troops.

The unit moved to several locations in southern England. The last location was in Eastbourne, the most bombed town on the south coast of England.

"We were deployed in two locations - the first one was on top of a hill on the outskirts of the town right beside an anti-aircraft battery. We were like sitting ducks up there, as every day at least one fighter-bomber would cross the channel at wavetop and fly directly over our camouflaged location. The aircraft would strafe the ground as soon it hit the coast and then drop some bombs on targets in the town. Soon after several attacks we moved to another location near the waterfront."

On Boxing Day. Dec 26. 1943 the unit members were told to pack their personal kit. From Eastbourne they moved to a holding camp at Chobarn. There they received malaria shots in preparation for deployment to Italy with the rest of 1st Canadian Corps. On Jan 6, 1944 the unit departed on a Liberty ship bound for Italy. The unit finally was going into action on the battlefield!

Fighting on the Battlefields of Italy

"We arrived in Naples during the middle of an air raid on Jan 15, 1944. From there we traveled by train to Bari where we picked up our equipment from the British equipment that had been used in North Africa. Then we moved north to join the rest of 1st Canadian Corps at Raviscannini approximately 15 miles south of the Cassino frontlines."

A shift of operators was sent to the front to work with 106 SW Type B section for training under battlefield conditions. This was the second time the two units had worked together.

A week later the unit took over 106 SW Section's tasks. The location was on the side of a mountain in an olive grove near San Pietro that was within 2-3 kilometres of the town of Cassino. The whole location was completely covered with camouflage nets. The soldiers lived in tents raised over three foot deep trenches.

From that position the unit observed the steady build-up of troops, trucks and tanks in prepa- ration for the attacks against the Gustav line. Soon it would experience its first taste of battle and one of it operators, Ed Marten, would have the unit's biggest scoop of the war as described at the beginning of this article.

After the battles for Rome the 1st Canadian Corps was sent to the rear for rest. But there was no rest for Number 1 Canadian SW. It joined with 107 British SW Type B to relieve 2 SW Type A at 8 Army HQ. This was necessary to allow rest for its personnel and the complete refit of equipment that had been in operation since November 1941. It also demonstrated the close working relations between the Commonwealth SW units.

"During this time King George VI visited the 8th Army. For his visit we had to go without fresh water for 24 hours so that the water could be used to water down the dusty roads! However, he did not visit the unit. Sir Oliver Leese,

8th Army Commander did later visit the section at Arezzo and thanked us for the work we had done in supporting the assaults to liberate Rome. Those who were off duty received a corncob pipe as a memento. I, unfortunately, was on duty and didn't receive one!"

In August 1944 the unit finally rejoined the rest of the 1st Canadian Corps who were in action around Florence. It then moved under secrecy (they had to remove all identifying marks from their equipment and uniforms) to the Adriatic coast to prepare for the next attack against the German defences. Unusually, the move was done in daylight due to the complete lack of German aircraft.

"The next location we moved to was close to the outskirts of Rimini on a ridge overlooking the airport. Here we could actually watch the fighting in the area. Intercept was nearly impossible here, as there was a battery of 25 pounders a few hundred yards behind us, but it was the only place available."

After four or five days of fighting the unit moved to Ravenna, which was the last location in Italy. The battle at this stage had slowed down due to winter and the unit stayed there until March 1945.

At that point it was decided to join the two Canadian Corps in Northern Europe. The 1st Canadian Corps moved out of the front lines. The SW Section turned in all its equipment, and moved by lorry to Naples. On 9 March 1945 the unit sailed for Marseilles, France, on a Liberty ship.

Joining the 1st Canadian Army in Holland

From Marseilles the unit members were moved by truck from Southern France to join the 1st Canadian Army. The move took five long days, going from one to another staging area until finally arriving in Belgium. There, the unit was outfitted with new equipment and vehicles.

On Mar 23, 1945 the unit was operational again and moved forward near the Corps HQ, which was located in the town of Nijmegen, Holland. The unit immediately went to work providing Intelligence as the Canadian troops advanced across the Rhine and swept across northern Holland. The unit moved three times in April behind the Allied advance. On the 27th of April, American and Russian troops met on the Elbe River near Berlin. In Holland a truce was arranged to allow the Allies to distribute food to fhe local population. On the afternoon of 4 May, the message was received that "All offensive action is to cease forthwith." By early evening an unaccustomed quiet settled over the troops in Holland. The next day the unit moved to Apeldoorn.

"I was on shift when the orders came to shut down for good intercept operations as the war was really over. I really cannot explain the feelings that came over me. It was a sense of relief, yet I did not shout for Joy at that moment. I just sat there and tried to absorb the event. A tot of rum was issued to everyone and then we celebrated. The war was finally over!"

On 16 May 1945 the unit move to Hilversum in preparation to be disbanded. At that time, a photograph was taken of the unit members, many who had been with the unit since Dec 1940.

Conclusion

Number 1 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type B constantly produced wireless intelligence in England and on the battlefields of Italy and Holland. In Italy, the unit was continually turning over information seized on enemy supplies, casualties, and routine communications. They successfully identified and located numerous enemy units, the Herman Goering Panzer Division clearly the most notable.

The unit had been strafed in England, and bombed and shelled in Italy and Northern Europe. However, throughout all of this destruction and death, not one member of the unit was seriously wounded or killed.

The accomplishments of this small group of Canadians were not spectacular deeds of heroism but involved gathering information on the enemy that resulted in substantial savings of Canadian lives. They were proud of their achievements and left the war with a feeling of satisfaction of helping defeat the Axis.

Major Bowes summarized this feeling felt by all SW personnel in the Canadian Army in his March 1945 report.

"Even though our achievements and successes have not, and never will be, brought to the attention of the public, as have the brilliant exploits of our brother-in-arms who are serving in Canada's traditional regiments, we have the satisfaction of knowing that our efforts have greatly helped in the bringing about of the downfall of the most ruthless military power the world had ever know".

Notes

- ↑ Originally Published in Communications and Electronics Newsletter 2002/07 Vol 44