Defence of Hong Kong and Canadian Signals

The Far East was the scene of one of the most tragic episodes of the War for the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals. In response to a request from the War Office for reinforcements for Hong Kong, men for "C" Force signals were hastily assembled in mid-October of 1941. By Christmas Day they were either dead or prisoners of the Japanese.[1]

Contents

Decision and Deployment

Japan, though allied to the Axis since September 1940, had remained neutral towards the European War. In 1941 relations between Japan and the United States deteriorated, and Britain, standing alone and at bay in Europe viewed the weakness of her position in the Far East with concern. Since the disaster at Dunkirk, every man and every gun was needed to repel the expected invasion at home. British Intelligence, however, believed that Japan would not attack Britain or the United States, but would join Germany in the war against Russia which had begun in June. War with Japan was of course a recognized possibility, though not a probability in the opinion of the military authorities. Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed Hong Kong could not be held or relieved in a war with Japan, but was swayed from his position before the request for aid was made to Canada. In any case the decision to seek reinforcements for Hong Kong was primarily a political one-to bolster Chinese morale, to encourage the United States, and to deter Japan-rather than a military decision.

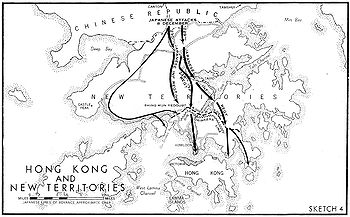

On 19 September the War Office requested one or two battalions to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. After serious consideration, the Canadian government agreed to the proposal ten days later, on the strength of British Intelligence's evaluation of the Far Eastern situation. Two battalions would be sent from Canada-not from the Canadian forces in England. On 11 October the War Office asked specifically for a brigade headquarters and certain specialist units, including a Signals section. Signals' contribution to "C" Force consisted of a number of operators and D.Rs. from the original 4th Divisional Signals at Barriefield, well trained in their respective trades but who had had little opportunity to work together as a Signals section. The whole Force comprised 96 officers and 187 other ranks, few of whom were fully trained for combat duty. Capt. G. M. Billings, then on detached duty from the 1st Canadian Corps Signals in England, was named to command the Signals section, but before he could even appraise his men the whole force was embarked on 27 October from Vancouver aboard the Australian liner Awatea and the escort vessel, H.M.C.S. Prince Robert. Because of hasty planning "C" Force sailed without its transport, and no vehicles had been received when the Japanese attacked 40 days after the departure from Canada.

The Force reached Honolulu on 2 November, and Manila 12 days later where the British cruiser H.M.S. Danae joined the Prince Robert as escort. On board ship every effort was made to maintain a training programme. Some of the officers at least realized that if war did come there was slight chance that the colony could be held for long against the superior numbers which Japan could throw into the battle. Training in small arms was therefore emphasized. Visual signalling practice was carried on by the Signals section, but no wireless practice was possible because of the necessity for radio silence.

Arrival and Preparations

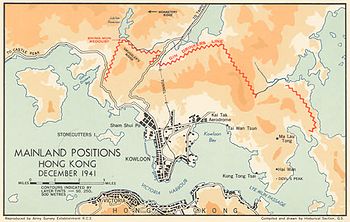

When the Canadian force arrived on 16 November, the Hong Kong Garrison was organized in two brigades, the first or mainland brigade, deployed for the defence of the Kowloon Peninsula, the second for the protection of Hong Kong Island. Brig. J. K. Lawson's Canadian Infantry formed part of the "island brigade", but the Canadian Signal Section was attached to Brig. C. Wallis and his mainland brigade which needed wireless to supplement fortress line communications. So small was the Crown Colony area that all the Canadians, whether serving on the mainland or on the island, could be billeted together. "C" Force Signals, intended solely to fill gaps in the Royal Signals Hong Kong Establishment, was a group of tradesmen, in which no orderly room or administrative personnel were included. In the actual fighting, however, they acted as a skeleton Brigade Signal Section and the lack of administrative personnel was very apparent as the Chinese civilians who were to be employed as cooks and batmen disappeared literally at the first shot."C" Force Signals was equipped with No. 11 and No. 18 sets for two battalions, but these sets were held for some time by the Hong Kong Ordnance which had unloaded them from the Awatea. The sets were subsequently released but no vehicles or motorcycles were made available to the section, and until the start of the fighting the section was limited for transport to the services of a station wagon loaned by Royal Army Service Corps when it was free from other duties. Nevertheless ingenious schemes were devised to familiarize men of the Signals section, particularly the D.Rs., with the terrain on the mainland and to give D.Rs, some practice in carrying messages, even without the benefit of motorcycles. The linemen were detailed to various Royal Signals Line sections and employed on fortress communications with which they had had little experience.

In addition to this limited training and the commitment to provide wireless communications for the mainland brigade, the section was responsible for instructing selected infantry signallers of the Royal Scots, 2/14 Punjabis and the 5/7 Rajputs in wireless. Despite the delay in getting release of the No. 18 sets from Ordnance these infantry signallers were trained to an elementary level in the field use of wireless. No training on maintenance was possible so that when sets broke down later in action they were discarded. In fact, however, the loss of these sets during the fighting on the Island was not of serious consequence since the Island was adequately served by fortress lines. The link to the Royal Navy, however, never operated simply because the Navy was too busy during the fighting to answer calls.

Attack on the Mainland - 8 December 1941

On 7 November Mr. Cordell Hull had warned the United States government that an attack by Japan might be imminent. Exactly one month later, the Japanese launched their infamous attack on Pearl Harbour. That same fateful day, 8 December (Hong Kong time), the mainland brigade had prepared a "manning exercise" as a test of operational efficiency. Thus, by accident, the Canadian Signalmen were at their posts, loading supplies into their only vehicle when Japanese planes raided the Kai Tak aerodrome and shortly afterwards bombed a prominent building in Sham Shui PO. Several signalmen were wounded, and it might be noted that while the Winnipeg Grenadiers lay claim to being the first Infantry unit of the Canadian Army to see action in the Second World Warj (11 December 1941), Canadian Signals actually suffered battle casualties three days earlier. Captain Billings immediately commandeered a number of civilian vehicles, and the D.Rs. obtained some motorcycles from the Ordnance Depot on Hong Kong Island. Thus the Signal Section got the transport which had previously been withheld. A D.R. service using five men was established and, despite occasional sniping by Chinese guerrillas, it operated successfully until the evacuation of the mainland.After the night of 10-11 December when the Royal Scots at Shing Mun Redoubt were overrun, the situation on the mainland deteriorated rapidly. With the permission of General Maltby, G.O.C. Hong Kong, Brigadier Wallis prepared to withdraw his headquarters to Devil's Peak, a strong defensive position on a peninsula and the last foothold on the mainland. Cpl. Charles Sharp had been ordered to evacuate a group of non-essential men and vehicles from the Rowloon Headquarters on 13 December. This entailed a drive to the ferry terminal through surprisingly heavy guerilla opposition. His charges safely aboard the ferry, Corporal Sharp attempted to return to the headquarters to report to Captain Billings. In this endeavour he was turned back by stiffening enemy opposition, and failed to get through even on foot. The remainder of the day he spent helping to engage enemy patrols. Eventually he crossed to the Island on a sampan whose crew he intimidated with his sub-machine gun. Some R.C.C.S. operators attached to the Royal Scots drove commandeered buses to assist in the evacuation of their positions.

At zero hour the remaining Signals and Headquarters personnel moved to the Kai Tak airport shoreline where small boats were waiting to evacuate them to Devil's Peak. When it became apparent to Captain Billings that the Brigade Headquarters transport and Signals motorcycles could not be evacuated, and were likely to fall into Japanese hands, he searched about for means of saving them. Brigadier Wallis agreed that Signals would not be needed at Devil's Peak which had line communications and permission was granted for volunteers to attempt a run to the vehicular ferry which would take them to the Island. At worst the equipment would be destroyed by enemy action. With motorcycle outriders, the half dozen cars and trucks loaded with Signals stores turned and raced to the dock through enemy-held territory in total blackout with only minor damage from enemy fire. Of their meagre equipment, Signals lost only a No. 11 set with the 5/7 Rajput Regiment, whose operators had had to destroy everything in their move to Devil's Peak. The Canadians had few line maintenance commitments, since this branch of communications was covered by the excellent permanent fortress installations under the control of Royal Signals.

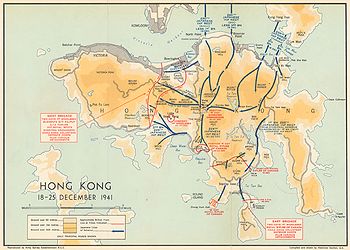

When the section had reformed at their billet, the villa Casa Bianca which served as the Island Signal Pool, a hot meal was prepared, the first since the Japanese had attacked, and the men enjoyed the luxury of several hours' uninterrupted sleep. Both brigades were now deployed for the defence of the island, and the Canadian Signal Section was attached to Brigadier Lawson's "West Brigade" for this phase of operations. Three days elapsed before the enemy crossed the strait and in that time an operational communications system was established. Needless to say, it functioned under constant aerial observation and shelling. Every attempt to use wireless brought down an immediate enemy artillery barrage. D.R. runs along the exposed roads on the north side of the Island to Victoria Headquarters were extremely dangerous in the days preceding and immediately after the Japanese crossing. Corporal Speller and Signalmen Damant and Thomas made many of these trips as volunteers and both signalmen lost their lives in the course of this duty when machine gunners caught them on an open stretch of shore road.

Attack on the Island - 18/19 December 1941

When the morning of 19 December dawned Japanese troops, who had landed at the northeast end of the Island during the night, were already pressing hard from north and south toward West Brigade headquarters at Wong Nei Chong Gap. Counter attacks were unable to stem the tide and the brigadier notified all concerned that a move to an alternative position was imminent. Such a position with line communications already prepared had been reconnoitred by Signals. An advance party was sent to the alternative position but so rapid was the enemy advance that there was no time for an orderly withdrawal of the skeleton staff at Brigade Headquarters. Small arms fire was raking the position and the staff was pinned down. Brigadier Lawson finally gave the every-man-for-himself order. Brigade troops were part way up the hill in rear of the position when they were fired upon from a pill box which they had believed to be in our hands. Each man crawled and fought his way up the exposed slope towards the intended new headquarters to the southwest. During one period Corporal Sharp and his men held a vital road position on their own initiative, stalling the Japanese advance in that sector until relieved by a larger force. Brigadier Lawson had delayed his departure to destroy documents and was killed soon after leaving the command shelter. When Captain Billings attempted to leave by the same route he was wounded but later he and the Staff Captain of the Brigade made their way in an abandoned vehicle travelling northwest to the Winnipeg Grenadiers headquarters at Wan Chai Gap.Signals detachments, many of them "walking wounded", now gathered at Wan Chai Gap. Shelling became indiscriminately heavy, and the men had scarcely settled into a villa when three of them were killed. The last scene of this tragic piece was played at Victoria Barracks. Remnants of Brigade Headquarters Staff and others, under command of Captain Billings, took up positions round about the barracks for a last-ditch defence of the area. Instructions were to stand or fall. For several days they patrolled an ever diminishing perimeter, fighting off Japanese attacks at close range. Shortly before noon on Christmas Day, however, they were ordered to lay down arms. This they did after destroying all equipment, including the last link with Canada, a high-powered wireless station working to England. The capture of Hong Kong had taken 18 days and had cost the lives of five of the 33 R.C.C.S. members who had deployed.

Aftermath

The surviving troops were fated to endure almost three and a half years in prison camps of indescribable squalor and horror. The small Signals contingent shared in all the misery, hunger and degradation. One member of the Signal Section died in January 1942 and three more died while Prisoners of War in the years following bringing the total casualties to nine, the highest percentage of casualties for any Canadian unit involved.

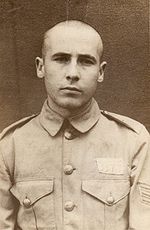

One of their number distinguished himself far beyond the call of duty. Sgt. R. Routledge assumed the perilous role of go-between for senior officer prisoners and Chungking agents. Messages concerning plans for mass escapes were passed by the sergeant on work parties. A Japanese agent intercepted one of these, and Sergeant Routledge was taken into custody. In the full knowledge that his predecessors in this venture had been executed, this N.C.O. refused to divulge the names of his colleagues, despite the torture, starvation and beating to which he was subjected.

Royal Canadian Corps of Signals "C" Force members

The R.C.C.S. contingent of the Canadian Forces sent to defend Hong Kong was one officer and 32 other ranks.[2][3][4]- L/Corporal R.W. Acton, (K/35409); Operator

- Signalman W. Allister, (D/116327); Operator

- Signalman J.D. Beaton, (K/35438); Despatch Rider

- Captain G.M. Billings; Commanding Officer; wounded G.S.W. right knee and right arm (Wong Nei Chong Gap) 18 December

- Signalman R. Damant, (D/3385); MiD; Despatch Rider; killed 19 December by shellfire

- Signalman R.N. Damours, (K/34935); Operator

- Signalman E.A. Dayton, (K/34722); Operator

- Signalman J.T. Douglas, (K/34017); Operator

- Signalman L.F. Dowling, (B/32015); Operator

- Signalman J.L. Fairley, (K/34910); Operator; wounded by shellfire and died of wounds on 22 December

- Signalman H. Gerrard, (P/7563); Operator

- Signalman G.C. Grant, (K/34730); Operator

- Signalman H. Greenberg, (H/38860); Operator; killed 19 December by shellfire

- Signalman A.F. Grimston, (K/35476); Operator

- Signalman J.E. Horvath, (H/38902); Operator; wounded by shellfire and died of wounds as POW January 1942

- Signalman W.G. Jenkins, (K/36026); Lineman

- L/Corporal C.M. Keyworth, (K/11054); Operator; wounded by shrapnel - left wrist (Ridge) 25 December

- Signalman T. Kurluk, (K/36009); Lineman

- Signalman J.S. Little, (K/34073); Operator; died as POW 3 (or 5) June 1942 from dysentery

- L/Corporal J.F. Mitchell, (B/31782); Despatch Rider

- Signalman H.E. Naylor, (P/7575); Operator

- Signalman W.G. Normand, (D/3389); Despatch Rider; hospitalized

- Corporal D.A. Penney, (K/34027); Operator

- Signalman T. Redhead, (K/83057); Operator; died as POW 30 September 1942 from dyptheria

- Signalman A.T. Robinson, (K/74567); Operator

- Signalman J. Rose, (K/34771); Operator

- Sergeant R.J. Routledge, (R/7541); DCM; Operator; wounded by shrapnel - back, shin bone, thigh and fore arm (Jubilee Buildings, Shamshuipo) 8 December

- Sergeant C.J. Sharp, (K/35468); MiD; Operator; killed 19 December by shellfire

- Signalman L.C. Speller, (K/83926); MM; Despatch Rider

- Signalman A.R. Squires, (K/80593); BEM; Lineman; wounded by shrapnel - elbow (Magazine Gap) 25 December

- Signalman E.R. Thomas, (K/34801); Despatch Rider; killed 19 December by riflefire

- Signalman G.J. (Blacky) Verrault, (D/116314); Lineman

- L/Sergeant W.J. White, (K/34757); Operator; died as POW 25 September 1942 from dyptheria/dysentery

Awards

There were five awards to R.C.C.S. members of "C" Force, three for events during the battle, a Military Medal and two Mentioned in Despatches and two, a Distinguished Conduct Medal and a British Empire Medal, whilst a POW.

Signalman R. Damant MID citation not found Sergeant R.J. Routledge DCM For devotion to duty and conspicuous bravery whilst on Special Service during his period of captivity as a prisoner of war in Hong Kong in the hands of the Japanese. From the middle of October 1942 contact had been established between officers of the Shamshuipo Camp and British Intelligence Officers [BAAG] at Waichow.

About the middle of May 1943, when the method of sending and receiving messages was through the medium of Chinese drivers of the ration lorries, it became necessary to replace the contact who had been dropped from the ration party, and consequently was no longer in a position to continue the service. Routledge was a member of this ration party who, without hesitation, volunteered to fill the vacancy. He showed considerable initiative and intelligence in performing the extremely difficult and hazardous duty of passing the messages under the eyes of the Japanese guards, when the slightest slip would have resulted in exposure leading to severe punishment, even to the loss of his life. He performed this service competently until the channel of communication was closed about the middle of June. This work was of the utmost value to the Camp, ensuring as it did the vital supply of medicine for the many sick in hospital and providing important information to the outside which was urgently required.

On the 1st July he was sent for by the Japanese Military Authorities and, suspecting the reason, he showed great initiative and presence of mind by giving the alarm to his fellow workers en route. He was removed from the Camp and taken to the Gendarmerie Headquarters and charged with communicating with the enemy. He was brutally beaten and suffered a variety of tortures including the Japanese "Water Torture" to endeavour to compel him to disclose the names of the officers directing these operations. In spite of incredible suffering he resolutely refused to divulge any information, and showed great courage and fortitude in enduring these repeated tortures for several hours before finally being removed to Stanley Prison to await Court Martial for espionage. The court sat on 1st December and after the statements were read the Prosecutor demanded the death penalty, but the Court awarded a sentence of 15 years imprisonment.

He was confined to Stanley Prison until 22nd June 1945, when he was removed to a Military Prison in Canton. He was returned to Hong Kong on 21st August and set free. The resolute courage of this NCO in spite of indescribable suffering, and his devotion to duty, provide an example in the highest tradition of the Service.

Sergeant C.J. Sharp MID Sergeant Sharp was a member of a signals detachment at Hong Kong in December 1941. On 13 December he was ordered to evacuate a group of men and vehicles from the mainland Headquarters at Kowloon. In order to do this, he drove with a convoy of four vehicles through Kowloon in the face of guerilla opposition. He then attempted to return with one vehicle to extricate his officer and certain signals personnel, but was prevented by enemy action. He then tried to return on foot but was driven back. He stayed on the waterfront until nightfall engaging enemy patrols and eventually crossed to Hong Kong Island on a sampan, whose crew he intimidated with a sub-machine gun. Later, on the island on 19 December, he and a signals party held an important road position on their own initiative, holding up the Japanese advance in that sector until he was relieved. His men were greatly outnumbered. His courage and leadership were exemplary, unflinching devotion to duty taking him into dangerous positions, and he performed his duties without a thought for his personal safety. Unfortunately on or about 23rd December he was killed by a shell striking the building in which he was billeted. Signalman L.C. Speller MM citation not found Signalman A.R. Squires BEM citation not found

See Also

- Heroes Remember - R.J. Routledge - a recount of his experiences related to C Force

- Beyond the Call - Hong Kong. An occasional blog about the book, "Beyond the Call", and the men of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-45.

References

- ↑ Majority of text on this page is from History of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals 1903-1961

- ↑ 90 Years and Counting

- ↑ Hong Kong War Diary

- ↑ Beyond the Call - RCCS Hong Kong Contingent