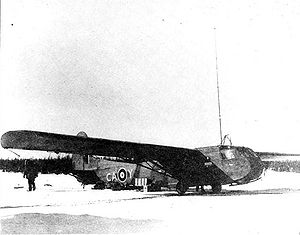

Glider, CG-4A, CA-Y

| Glider, CG-4A, CA-Y | |

|---|---|

| Fly in radio station CA-Y | |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 3,700 lbs (empty) 7,500 lbs (gross) |

| Length | 48 ft |

| Width | 84 ft |

| Height | 13 ft |

| Crew | 2 |

| | |

| Speed | 150 mph (max) 44 mph (stall) |

In the early 1950s, the Canadian Army airborne role was emerging as defence of Canada operations, primarily in Canada's north, as a primary component of the ALCANUS (Alaska, Canada, US) joint force. At the time, parachute airlift was limited to the Douglas C-47 Dakota; pending Canada's acquisition of the Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar. Limited, for although the Dakota was capable of lifting infantry, Signals needed something more suited for heavy lift. Radios were typically large cabinet affairs, with high energy demands and large antennae structures, and were thus simply beyond the effective capability of the Dak. the Boxcar would meet those requirements.

Development was underway, of the Radio Station AN/GRC 501 based on the 6000-pound load bearing platform, a platform designed for heavy load parachute delivery from the 119. In the interim, a CG-4A glider, registration CA-Y, was taken from war stocks and adapted as a fly-in radio station. The glider was crewed by two pilots, generally of S/Sgt rank, and crewed mainly by members of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps.[2] On operations, two radio operators would deploy with the glider, with the balance of the Signals unit deploying by parachute.

CG-4A Glider, Hadrian

The CG-4A (US designation Waco) was the primary US Army Air Force glider during the Second World War. It was constructed of wood and steel: the wings and tail assembly of wood, the fuselage of tubular steel, plywood and fabric. The fuselage is best described as a large crate, crewed by two pilots seated at the front end. The nose was hinged just aft of the pilot's seats, thus allowing it to be rotated upwards to facilitate unloading from the front. Visualize the two pilot's seats and flight controls rotating upward, and a jeep with a 75mm Pack Howitzer driving out; this being a common load in Airborne operations. In closed of flying configuration, the nose would be held in place with latches, securing the nose compartment to the main fuselage frame.

The primary tug aircraft was the C-47, although in the second World War, a number of obsolete British bombers had been converted for towing use. A tow line, attached from the rear of the tug to the nose of the glider, completed the tow combination. When cast off, the glider would be flown to a landing site where it would remain until recovered. Recovery would be effected through a snatch system where the ground crew would set up a line assembly suspended from two poles. The recovering aircraft would approach at low level with a hooking device extended. The recovery line would be snared... the tow line secured to the tub... and in quick sequence the glider pulled aloft.

The Signals glider was permanently modified as an operating station; design and fabrication carried out by the Canadian Army Signals Engineering Establishment,[3] Ottawa. VHF radio linked forward to maneuver units. HF and LF provided higher formation and national rear links. Three 50-foot masts supported wire antenna, and strong points were installed on the glider for mounting vertical ground wave antennas. VHF equipment included the AN/PRC 509 and 510. HF, the RS 52 rated at 100 watts on CW; and LF, the AN/GRC 503 rated at 300 watts, CW only. HF antenna included the standard 34 foot vertical; horizontals: the dipole, Wyndome, and long wire configurations. LF employed a wire "T" comprising 300 ft horizontal and 60 ft vertical sections, center fed. A collapsible box kite was included as a long wire alternative. Line signaling, comprised a UC-10 switchboard and line holdings of 20 miles of don-8 field cable. (WD-1 was just emerging in US Inventories.) A bank of lead acid batteries was installed for DC power. Charging equipment power sources were based on standard four stroke generators. Fuel and spare parts completed the package.

February 1952 Incident

An incident of note occurred in February 1952. The The Active Force Brigade Group Signal Squadron, later 1 Airborne Signal Squadron, Kingston, participated in Exercise Sundog III at Fort Chimo Quebec in support of R22eR. Staging area was Goose Bay Labrador. The Signals glider was flown from Ottawa to Montreal, then to Goose Bay. the Signals NCO I/C was then Cpl K.E.P. Tyerman, Operator Wireless and Line. (Ed later re-mustered to Radio Mechanic and retired in the 70s as an MWO Foreman of Signals... F of S by qualification, not appointment). En route to Goose, the latches securing the nose of the glider inexplicably released. Through what can only be described as outstanding airmanship by the pilots, and the quick reaction of Cpl Tyerman, disaster was stayed.

As reported by MWO (Ret'd) KEP Tyerman

"In early January 1952, I was sent to National Research Council Ottawa to help in fitting out a CG-4A glider, to provide communications for Airborne troops in the far north. We installed a high frequency RS 52, receiver and transmitter, and an AN/GRC 503 low frequency transmitter and receiver, with all the necessary batteries and support equipment. This took about one week. I returned home to Kingston for the weekend, with instructions to be back with full arctic gear to go with the glider to Goose Bay. On Sunday, I received a phone message to get the early morning train from Kingston to Montreal, and to make sure that LCpl Mel Dobbey was with me. We would be met and taken to Dorval Airport where the glider was now located. Mel and I arrived at Dorval and met the two glider pilots. They told us that they had taken the glider for a test flight that Sunday at Ottawa. The weather closed, so they diverted to Dorval. The four of us boarded the glider with the tow rope connected to the C-47 and had a normal take-off.

About three hours into the flight to Goose Bay, the glider made a loud noise, the floor opened up about two feet, with very cold ari now buffeting us. We tried very hard to get the nose to close. The two latches had failed and the nose was opening and closing, but not closing better than two feet at floor level. The top was still firmly attached by hinges to the main body. The pilots tried to trim the glider to close the nose but were having difficulty keeping level flight. Mel and I opened the line container (don 8) and wrapped line between the two parts to try to secure the nose and close it. We managed to close it about 6 inches but the constant pull from the tow line was holding the two parts apart. We wrapped all our cable to keep the nose from opening more. It was extremely cold, especially by the open floor, so we moved to the rear of the glider cargo compartment ot help keep the tail down and to get out of the cold air stream at the opening. We noted that the tow plane knew we had a problem as the drag on in had increased. We carried on to Goose Bay and as soon as the tow line was released, the nose closed. We landed safely and were taken to a hanger. It was then that we realized how cold we were. The next day, I was selected to leave for Fort Chimo whit the pathfinder group, jumping with a Eureka beacon to set up and guide the main lift in. Three days later, the main force jumped and the glider came in without any problems."

Addendum

On analysis, it has been concluded that the constancy of colour on the ground, that is to say, the whiteness of snow, plus the severe cold winter air, kept thermal activity to a minimum. Thus, although the stresses imposed on the glider and the tug were significant, the pilots (tug and glider) by hard work and consummate skill were able to maintain a flying attitude. Had it been summer, thermal activity would have been much more pronounced and violent and in all likelihood the result would be turbulence beyond any pilot's ability to maintain safe flight. In all probability, if the tug/tow was continued, the glider would have suffered catastrophic damage, literally being town apart. If released, probably lost and destroyed in the remote forests of Quebec, north of the St Lawrence. It can be safely assumed that by attempting to secure the two sections of the glider with the telephone cable, Cpl Tyerman and LCpl Doobey contributed much to averting a disaster.

References

- ↑ Page text provided by Bob Janik.

- ↑ For the 28 Canadian Army Glider Pilots known to CanadianArmyAviation.ca, their parent Corps were: Infantry: 13; Royal Canadian Army Service Corps: 5; Royal Canadian Engineers: 4; Royal Canadian Artillery: 2; Canadian Intelligence Corps: 1; Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps: 1; Canadian Parachute Corps: 1; and one who transferred to the RCAF and their previous Corps is unknown. Glider Operations in the Canadian Army. CanadianArmyAviation.ca, accessed 17 February 2021.

- ↑ At the time of the work, the unit was known as "Canadian Signals Research and Development Establishment"